College or university: experts discuss the education choices of Nizhny Novgorod youth

Over ten thousand young residents of Nizhny Novgorod have submitted applications to colleges. According to the "Gosuslugi" portal, which processes applicants' documents, by mid-July 2025, the number of applications had already exceeded six times the total number of applications submitted during the entire 2024 admissions campaign. At the same time, the admissions campaign is still ongoing. Documents for full-time education are accepted until August 15, and for creative specialties—until August 10.

Today, the most in-demand fields among ninth-grade graduates who successfully passed the state final certification are: information systems and programming, law, economics and accounting, tourism and hospitality, and operational logistics activities. It is worth noting that the competitive scores for admission to Nizhny Novgorod colleges and technical schools are quite high and continue to grow each year.

We asked experts to evaluate the explosive growth in requests for secondary vocational education in the Nizhny Novgorod region, exploring the reasons behind this boom and its potential medium- and long-term effects.

Andrey Samsonov, researcher at the Volga branch of the FNIAC RAS, senior research fellow at the ANO "Research Institute of Social Management Problems":

"The reasons for the growing popularity of secondary specialized education can be considered in two contexts. The first is the national trend related to changes in the economy and labor market. Here, several social processes developed in parallel and seemingly independently converged.

Firstly, the explicit degradation of vocational training in the late 1980s and early 1990s led, on the one hand, to a gradual decline (natural attrition) of specialists with secondary vocational education, and on the other hand, to employer advertisements, which even became the subject of jokes demanding university degrees regardless of the position offered. As a result, this niche was quickly filled by 'commercialized' universities that essentially began 'trading' diplomas in specialties previously accessible to workers with secondary education and 1-2 years of training. Consequently, the notorious 'office plankton' became the owners of university diplomas: accountants, sales and HR departments, technical and service staff, and much more.

Secondly, a peculiar 'fashion' for higher education emerged as a result of these sentiments and the outright unpopularity, low pay, and low prestige of manual trades. The economic situation allowed for minimal or, more accurately, 'reserved' specialists, prepared by the Soviet system.

By the early 2020s, these trends converged, and the country (and region) swiftly experienced a deficit of specialists in nearly all manual professions and qualified professionals. Geographically and infrastructurally, and considering the remaining highly professional personnel, the Nizhny Novgorod region can claim the role of a training center not only for its own needs but also for many neighboring regions. In the long run, this could prove to be as effective for regional development as large-scale projects like 'Neymark' and others."

Andrey Chugunov, journalist:

"The growth trend in 2025 in the number of ninth-grade graduates in Nizhny Novgorod choosing secondary vocational education (SVO) is driven by a complex set of factors reflecting both changes in educational policy and transformations in the labor market.

Firstly, the number of state-funded places in colleges and technical schools in the Nizhny Novgorod region has increased. According to the regional Ministry of Education, nearly 800 additional spots will be available in the upcoming academic year, allowing about 17,500 students to enroll in free secondary vocational education institutions. Overall, more than 30,000 places are accessible to applicants.

Secondly, society's perception of SVO has changed. Today, colleges and technical schools offer modern curricula focused on practical skills that meet labor market demands. Moreover, students in SVO often receive job offers even before completing their courses, enabling them to gain financial independence years earlier than their peers who choose university paths.

High demand and perceived salaries for manual trades like welders, turners, and electricians are directly related to the needs of manufacturing enterprises, although they do not yet strongly influence high school graduates to choose these professions.

Nevertheless, the increase in applicants for SVO in Nizhny Novgorod in particular indicates that attending technical colleges and vocational schools is becoming not just an educational choice but also a strategic decision for young Nizhny Novgorod residents seeking successful careers in a rapidly developing region."

Evgeny Semenov, Deputy Chairman of the Nizhny Novgorod Regional Public Chamber, Head of the Nizhny Novgorod branch of FòRGO, political scientist, Candidate of Political Sciences, Associate Professor:

"The sixfold increase in ninth-grade graduates applying to colleges and technical schools is an all-Russian trend. This was recently discussed at a meeting attended by Russian President Vladimir Putin, where Vice Prime Minister Dmitry Chernyshev spoke. Evaluating the emerging trends in the Russian education system in 2025, the vice-premier stated that 62% of ninth-graders have opted for college education.

Therefore, it is clear that the Nizhny Novgorod region, demonstrating a sixfold growth, has once again become a leader in a process that has recently attracted particular attention from the president and the government.

However, it must be noted that for many young people today entering colleges and technical schools, university doors remain open. After 3-4 years in SVO programs, they will return to university classrooms for another four years in bachelor's programs or five years in specialist programs. In total, this entails from 7 to 9 years of higher education.

It is highly likely that most of these students will not pursue master's degrees. Moreover, an informal dismissive attitude toward bachelor’s diplomas has developed in Russia. By analogy with the former Soviet education system, a bachelor’s degree is considered incomplete higher education. So, what is the way out?

Universities might offer alternatives—distance or evening education. While this undoubtedly saves time, the quality of distance learning in Russia has significantly declined, especially after COVID-19, when online models essentially destroyed the educational process. Many universities now treat 'correspondence' programs as a relatively honest way to extract money from students, turning them into a formal diploma factory.

I believe the response to this emerging challenge could be a definitive rejection of the two-tier education system imposed by the Bologna Process. Perhaps, in implementing higher education reform, it would be necessary to completely abolish bachelor's and master's programs and recreate a unified model of higher education in Russia."

Elena Mozgunova, historian, Ph.D. in Political Sciences, Associate Professor at the Nizhny Novgorod Institute of Management—branch of RANEPA:

"For a long time, a stereotype prevailed in our country—that a person cannot succeed without higher education. Millions of parents, exerting maximum effort, aimed to ensure their children’s admission to university. Education specialization was not always the main factor; the 'diploma' itself was what mattered. Consequently, thousands of university graduates do not work in their field.

A quite reasonable question arises: why all these efforts if many job vacancies do not even require a university diploma? Currently, a shift is occurring, with some young people from the 'Zoomer' generation considering higher education outdated and unnecessary for self-realization. Society’s attitude toward SVO as a secondary or inferior option is changing too.

I believe several reasons explain the surge in demand for secondary education in Nizhny Novgorod and Russia as a whole: rising university costs, increasing number of state-funded places in colleges, and most importantly, the opportunity to quickly access a profession amid ongoing labor market transformations."

Sergey Sudyin, Doctor of Social Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of General Sociology and Social Work at Nizhny Novgorod State University named after N.I. Lobachevsky:

"Of course, a sixfold growth is hard to explain solely by the traditional fear of graduates regarding OGE, EGE, and related difficulties. Most students from colleges, technical schools, and vocational schools, who resolved their conscription issues, boldly enrolled in SVO programs to later attempt to enter similar programs in universities by passing entrance exams. Concurrently, they could acquire a profession with a good chance of becoming their lifelong career.

However, such explanations alone are insufficient, especially since students are aware of how extended their training periods are.

What else has played a role? I think vigorous advertising of manual trades demanding not just basic operations but also specific engineering competencies, skills with complex machinery, and equipment. Clearly, with nine classes completed, there’s little to do at a modern enterprise: perhaps only waste disposal. And more likely, this is now automated, not manual.

In general, why study for so long when one can start working at a factory almost immediately after school and earn a decent salary?

The SVO system should be welcomed; after all, it means not just standing on the street, but acquiring a profession, developing, and restoring a previously damaged system of professional training. What concerns me is the recent emergence of strange—dare I say—initiatives that threaten serious issues for both school and higher education. That is truly dangerous.

Reducing school years will inevitably lead to a decline in the quality of future university applicants, including those entering SVO programs. Will they even go to technical schools, colleges, and vocational schools given the current underdevelopment of professional priorities? Educational policy regarding higher education could face significant upheavals. A sharp reduction in admissions for some of the most popular fields—even on non-budget basis—might make universities and institutes face serious difficulties. After all, universities are not only students, campuses, classes, and science; primarily, they are people, highly qualified personnel whose well-being depends on enrollment numbers.

In conclusion, one cannot improve one system at the expense of another."

Другие Новости Нижнего (Н-Н-152)

Footballer Daniil Lesovoy joined the Nizhny Novgorod club "Pari NN".

The agreement with him is valid for three years.

Moscow Dynamo midfielder Daniil Lesovoy has become a player of Pari NN, according to the Нижегородская команда telegram channel. 17.07.2025. Time N. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

Footballer Daniil Lesovoy joined the Nizhny Novgorod club "Pari NN".

The agreement with him is valid for three years.

Moscow Dynamo midfielder Daniil Lesovoy has become a player of Pari NN, according to the Нижегородская команда telegram channel. 17.07.2025. Time N. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

Processing fields

LLC "Agroholding KPI" (hereinafter – the Company) in accordance with the Federal Law "On Beekeeping in the Russian Federation" notifies of July 17, 2025. Sechenovsky Municipal District. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Sechenovo.

Processing fields

LLC "Agroholding KPI" (hereinafter – the Company) in accordance with the Federal Law "On Beekeeping in the Russian Federation" notifies of July 17, 2025. Sechenovsky Municipal District. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Sechenovo.

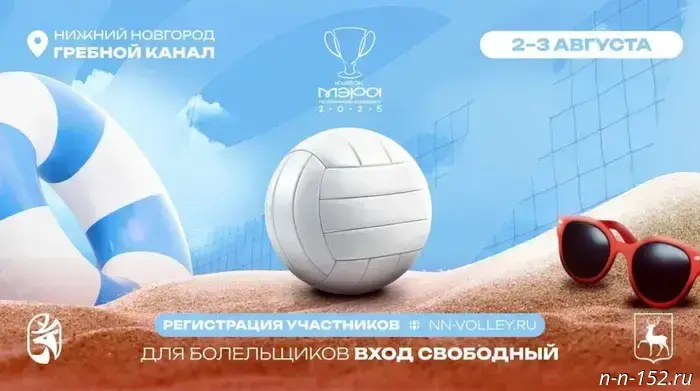

The Mayor's Beach Volleyball Cup will be held for the first time in Nizhny Novgorod.

Guests will have the opportunity to personally interact with beach volleyball stars

From August 2 to 3, the first Mayor's Cup of Nizhny Novgorod for amateur beach volleyball will be held on the embankment of the Rowing Canal. 17.07.2025. City Day Newspaper. Nizhny Novgorod. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

The Mayor's Beach Volleyball Cup will be held for the first time in Nizhny Novgorod.

Guests will have the opportunity to personally interact with beach volleyball stars

From August 2 to 3, the first Mayor's Cup of Nizhny Novgorod for amateur beach volleyball will be held on the embankment of the Rowing Canal. 17.07.2025. City Day Newspaper. Nizhny Novgorod. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

The trial launch of the new fountain took place in the park near the Serge Ordzhonikidze House of Culture.

The trial launch of the new fountain took place in the public space improved under the national project near building No. 17 on Chayadeva Street. 17.07.2025. Administration of Nizhny Novgorod. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

The trial launch of the new fountain took place in the park near the Serge Ordzhonikidze House of Culture.

The trial launch of the new fountain took place in the public space improved under the national project near building No. 17 on Chayadeva Street. 17.07.2025. Administration of Nizhny Novgorod. Nizhny Novgorod Region. Nizhny Novgorod.

Bastrykin will investigate the case of teenage extortion in Vyksa

Bastrykin will investigate the case of teenage extortion in Vyksa

The State Labor Inspectorate has shown interest in the fatal accident in the Vorotynsk district.

The State Labor Inspectorate has shown interest in the fatal accident in the Vorotynsk district.